|

I first thought of writing for siphoned demijohns in December 2021. I was playing with a pair I had bought at a charity shop, testing their pitch to see if they’d work for a Filthy Lucre concert I was producing. I sped up the process by siphoning the water, rather than pouring it. I loved the sound, and my obsession was sparked.

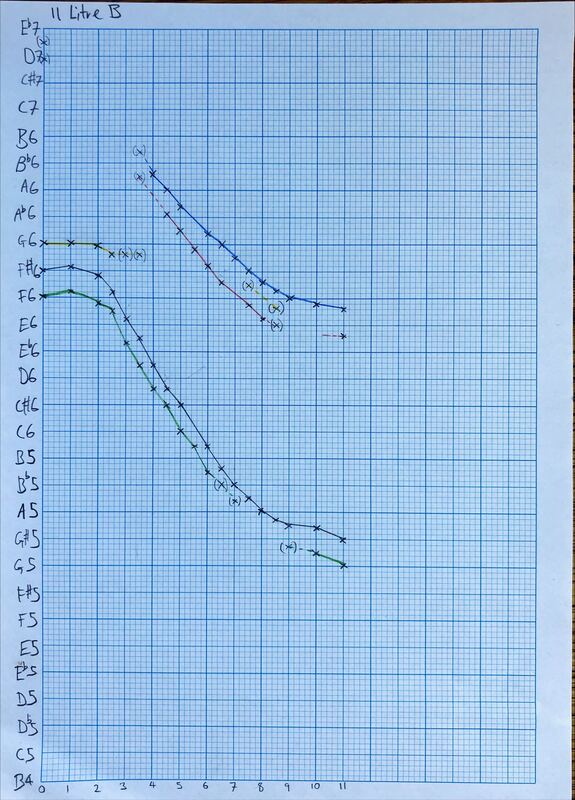

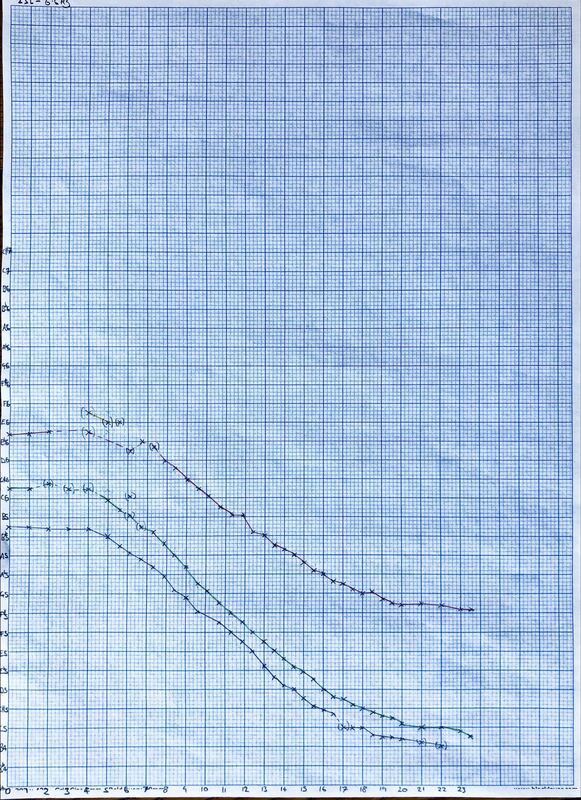

Step 1: Tunings I was immediately struck by the complexity of the pitches these demijohns produced when struck. There were at least two pitches occurring each time, but they were normally close to each other, so they were hard to pick out. I realised that my ear would be insufficient. Instead, I used a spectrogram. This shows all the frequencies that are present in a sound, enabling me to decipher the most important pitches. I poured the water in, half a litre at a time, checking the frequencies each time. This is what that looked like for the 23-litre vessel:

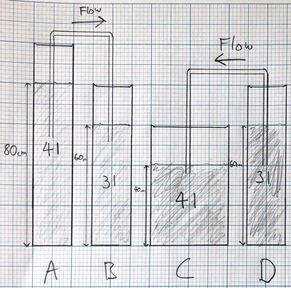

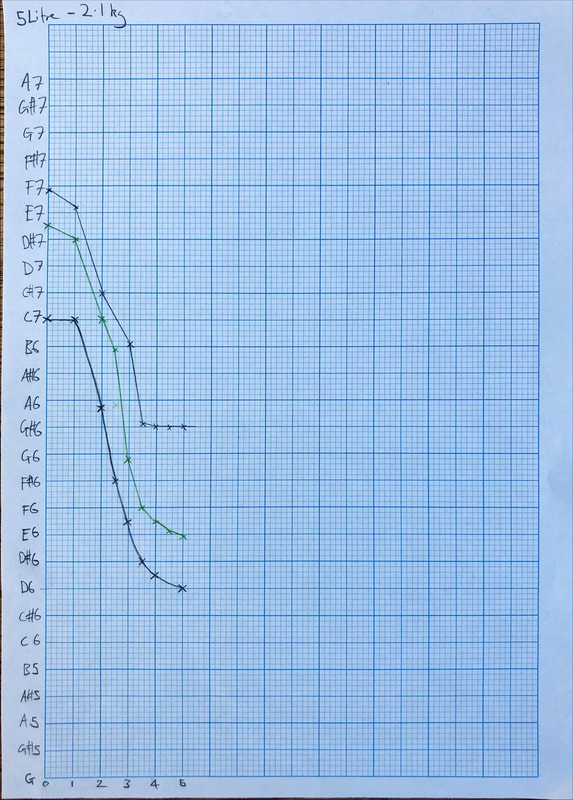

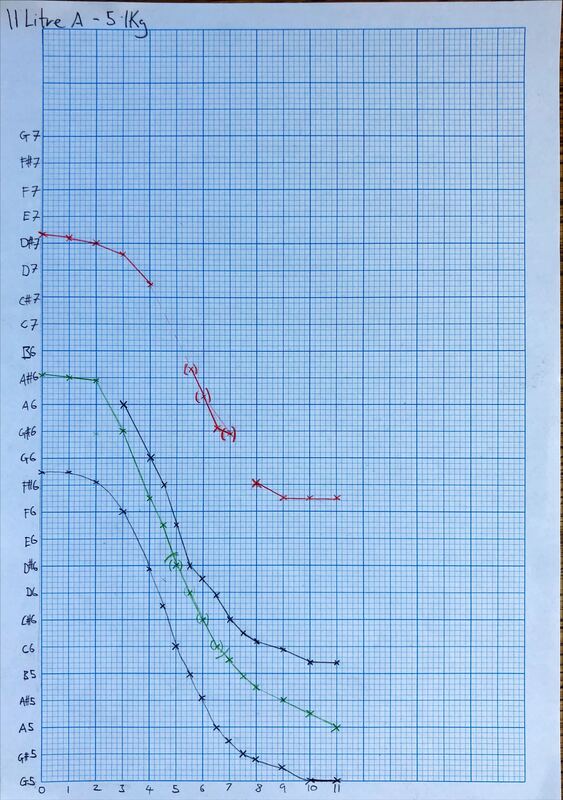

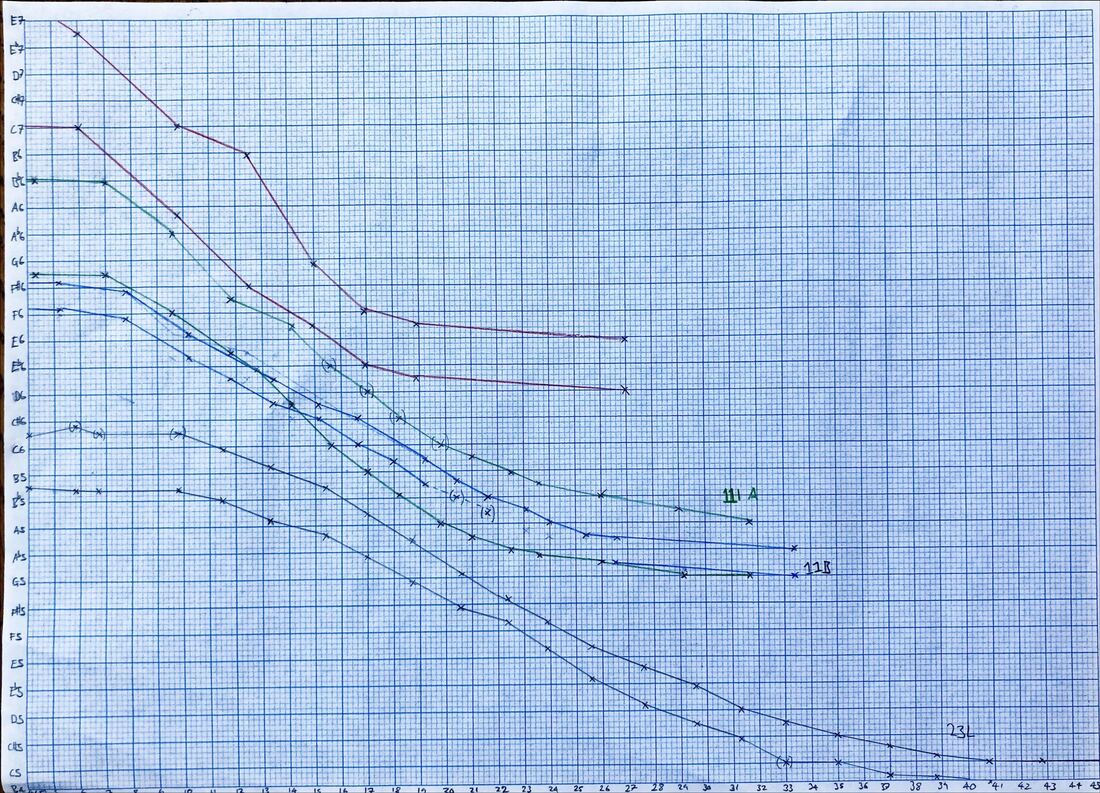

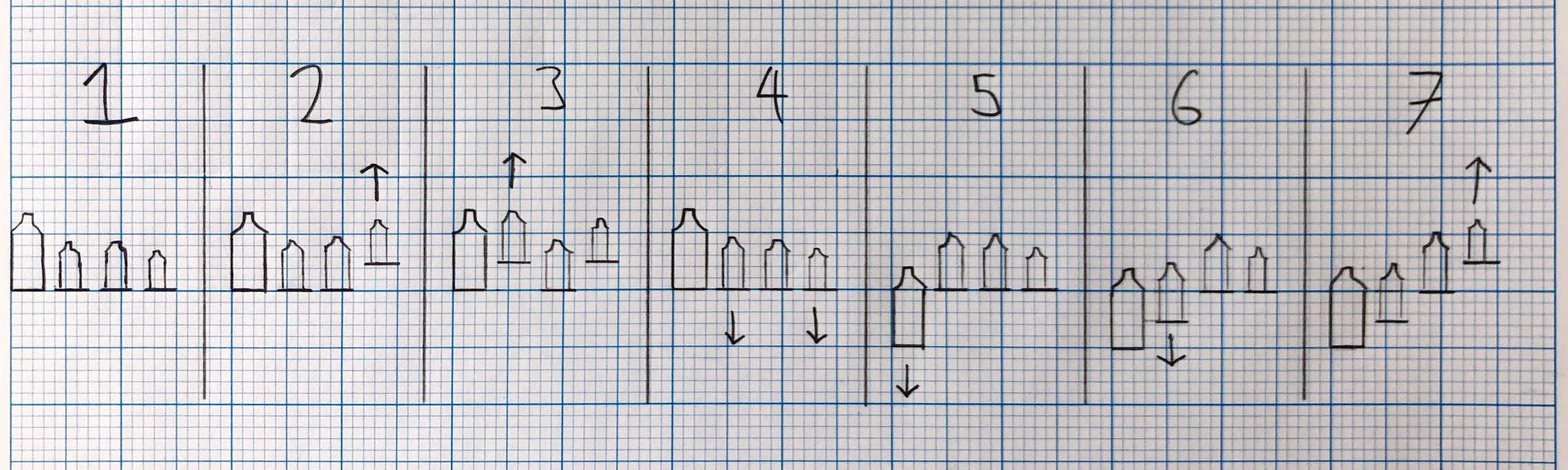

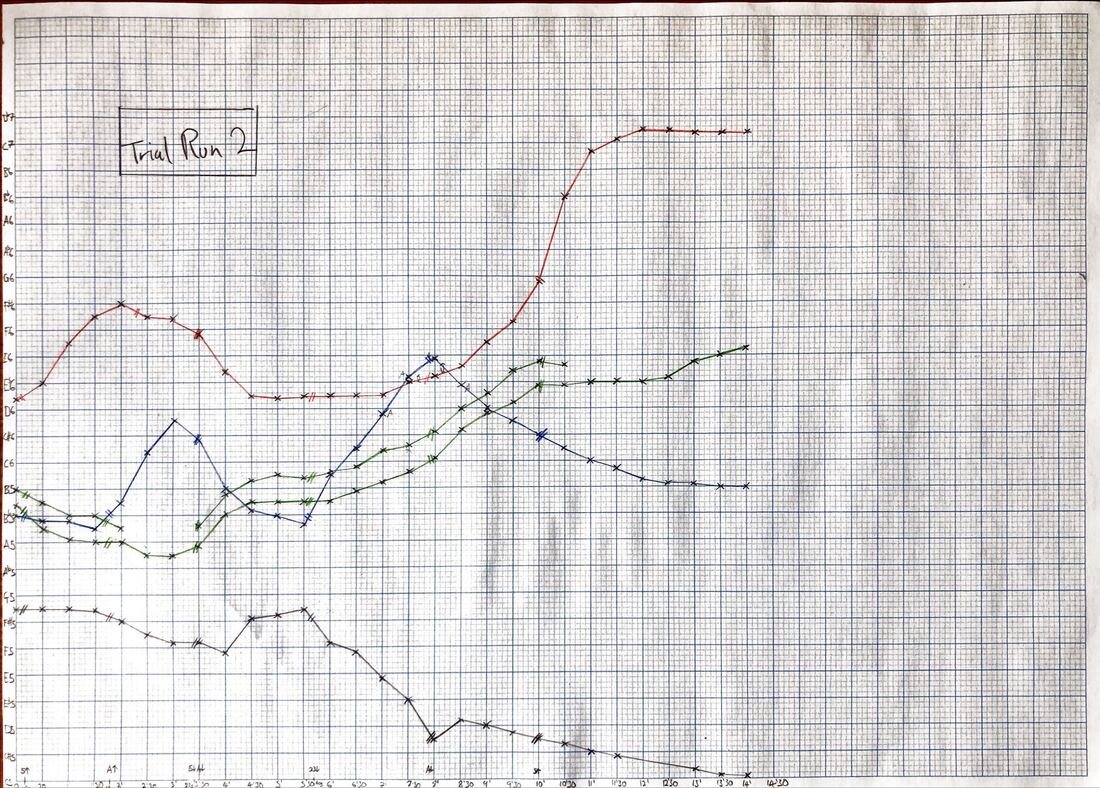

Step 2: Water Levels  This process gave me a sense of the ranges and pitch-compositions of the vessels. But when using siphons, it is the height of the water, not the volume of water, that determines flow. To put it another way: the water will flow from a vessel with a higher water level into a vessel with a lower water level until their levels are equal, regardless of the volume of water in each vessel. Left is a stylised example: in the system on the left, water will flow out of vessel A and in to vessel B, as vessel A’s water level is 20cm higher. The system will stabilise when both vessels have 3.5l of water at a level of 70cm. In the system on the right, water will flow out of vessel D into vessel C, as vessel C’s water level is higher. The system will stabilise at a water level of 46.66..cm, with 4.66..l of water in vessel C and 2.33..l of water in vessel D. So, to work out how my system was going to work, I’d need to work out how my pitch:litre lines would convert into pitch:cm. The first step was to work out litre:cm, by measuring the marks I’d made on the vessels earlier. This then allowed me to plot a pitch:cm graph: this contained all four vessels. Each vertical slice of the graph shows both a chord and an equilibrium state for the siphon system, as each vessel would contain the same amount of liquid. I then perused this graph for a nice chord. This would be the starting state of the piece. I settled on a 19cm starting state, which meant filling the system with a total of 25 litres of water. Step 3: State Changes The next step was to think about how to move the vessels to create the flowing siphons I was after. I could use my pitch:cm graph to help, using a simple equation to work out where each vessel would end up. I settled on a simple set up: I would be able to raise or lower the vessels by 10cm, except for the 23l vessel, which I’d be able to lower by 25cm. I then devised an order in which these shifts would take place: first I’d raise two vessels, then lower them back to the starting point. Then I’d lower two vessels, and finally I’d raise one vessel. This ending, with the largest vessel lowered and the smallest vessel raised, would drain the uppermost vessel: a fitting end to the process. Step 4: Pitch Over Time One last set of graphs remained. The flow of water through the siphons is not linear. The bigger the height difference between the vessels, the faster the water flows; the siphon rate slows as it nears equilibrium. To determine the impact of this on my state changes, I ran two recording tests. In these, I recorded myself playing each vessel once per second. I then went back to this recording and looked at the spectrograms to generate a graph of the state changes for the whole piece. This graph and its accompanying recording were my touchstone while writing: they show the pitch of each vessels at each moment of the piece. Step 5: Write the Music

It wasn’t until all this preparatory work was complete that I could begin writing, as without it I didn’t have any sense of the pitches I was working with. It was, without doubt, the most arduous pre-composition work I’ve done to date, but I found it completely absorbing. I came out of it with one major piece of advice: if you’re working with water, use digital scales not measuring jugs! They’re so much more precise. Until I switched to them, I made many measurement mistakes.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

NewsYou can find out about recent and upcoming projects here, and stay up-to-date with email or RSS below.

Archives

July 2024

|

|

All photographs by Ilme Vysniauskaite

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed