|

I’ve enjoyed writing music for how to go outside, a play written and performed by Kay Dent and directed by Jesse Haughton-Shaw. It’s a wonderful piece of writing. It takes the form of a guided meditation – a common feature of our digital landscape that, in Kay’s work, is warped into an exploration of loss. It’s uncomfortably intimate: the meditation guide is somebody who we’ve learnt to give our attention to but also to ignore. I’ve written a lot of music for this play – upwards of twenty minutes! You can hear a demo of part of that below, or even better, in context this week. The show is on YouTube live, Wednesday to Saturday at 8pm, and lasts 50 minutes. Tickets are available here.

As a composer, this piece presented interesting compositional challenges, which I thought I’d talk about here.

The most stimulating challenge was finding the right mood for my work. The show discusses strong emotions but often does so indirectly. I knew I wanted to do something that tapped into guided meditation’s rhythmic breathing and some of its the associated generic tropes. As such, the music is built around a chord progression for viola duo, with simple chords gradually accumulating in time with the guide's breath.

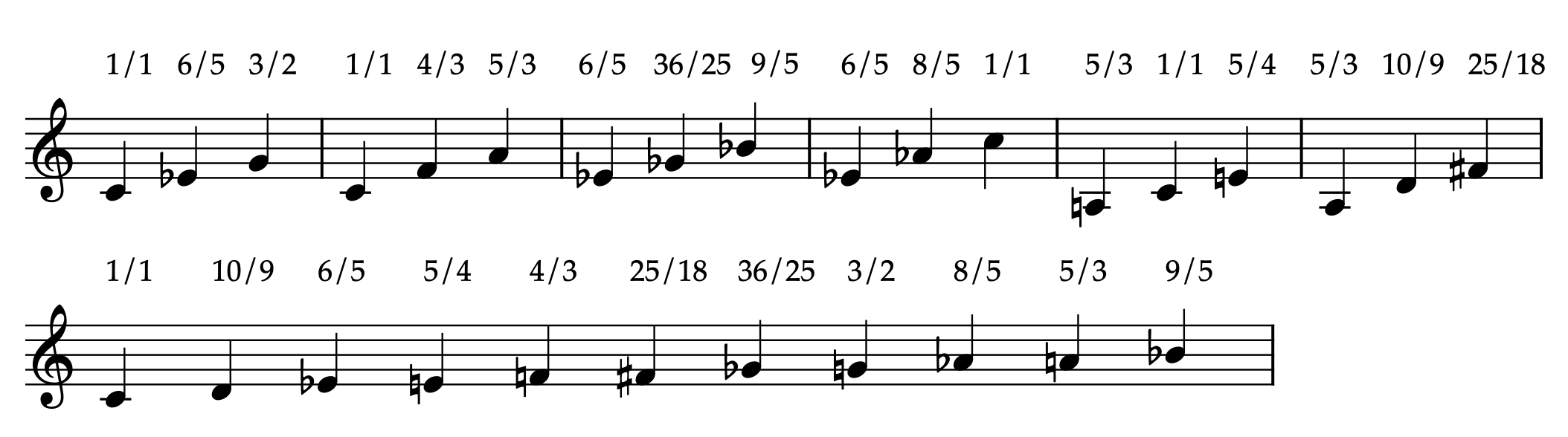

One challenge I faced was keeping the music suitable for a background underscore and reminiscent of meditative music without become cheesy or bland. An approach that relied too heavily on stock harmonic ideas would, I felt, undermine the emotional subtlety of the work. And I wouldn’t enjoy writing it. My solution to this was to use Just Intonation (JI). JI is a way of tuning notes that used to dominate Western music, and which is used in many other parts of the world. It involves creating simple ratios (like 3:2) between the frequencies of notes rather than equally dividing an octave into twelve notes. This approach produces very pure, beautiful chords throughout most of a key. But it also creates some pairs of notes that clash wildly if played together. I felt I could exploit this feature to create music that was mainly resonant and beautiful, but that was sometimes strangely off-kilter. I drew on a harmonic system I’ve used before, in my piece Some Parts of Us. It uses three pairs of chords, centred around C minor. C minor is pair with F major, A minor with D major and E flat minor with A flat major. These pairs create three Dorian key areas, on A, C and E flat, and an 11 note scale. The scale can be seen as a C minor scale plus a D Mixolydian scale, with an extra G flat. You can hear and play with this Justly Tuned scale here, courtesy of Leimma. (Leimma has been a massive help in facilitating this composition, as it allowed me to play with these ideas more fluently.) Here is the scale, first as I generated it, using simple triads, and then as a scale:

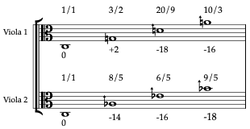

This scale inspired two viola tunings. The first is very similar to our usual tuning, but the D and the A are tuned as a 20/9 and a 10/3, rather than the typical 9/4 and 27/16. This tuning makes the gap from G to D howlingly out of tune. I exploit this tuning at key moments in the score. Having introduced the G (3/2) and the D (10/9) in contexts where they are in tune, playing them together is a lovely trick, like you’re looking at an old acquaintance in a shocking new light. The second retuning is rather more typical. It is a minor (or utonality) tuning, similar to that used in Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante. The top three strings are all moved up a semitone.

As I was working with just one player (the wonderful Jordan Bergmans), this two-tuning approach necessitated over-dubbing. This recording approach, where multiple recordings are layered on top of each other, was the key to generating enough material for the play. The play is 50 minutes long, and a great deal of it is underscored. While some of that length could be achieved by the use of loops, I was wary of the music seeming too repetitive or aimless. Overdubbing allowed me to make the most of all the material we recorded. Often the same bit of music (like the opening chords, which imitate a rising and falling breath) are used in entirely different contexts elsewhere in the work. There are some moments of this where I’m particularly proud of my economic reuse of material. How to be with her uses just twelve bars of fairly simple new material to create an 18-bar, five-voice texture, which, when looped carefully, takes up three and a half minutes of the play.

I think this material is promising, and I hope to return to it to produce a full OST recording sometime soon. In the meantime, do enjoy the demo, and come join us for the show!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

NewsYou can find out about recent and upcoming projects here, and stay up-to-date with email or RSS below.

Archives

July 2024

|

|

All photographs by Ilme Vysniauskaite

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed